Liverpool’s history has some fascinating twists and turns, one of which unexpectedly leads right onto the stage. If you’re familiar with Shakespeare’s name but not his stomping grounds beyond London, it’s worth taking a peek into Liverpool’s theatrical life. There’s a festival here that proves our city can also be a significant theatrical spot on the map of Shakespeare’s legacy. Find out more at liverpoolski.com.

The journey to Shakespeare in this city didn’t begin in the 21st century, nor even the 20th. The story has deeper roots: as far back as the 16th century, a patron emerged from Liverpool whose support, according to the BBC, proved crucial to William Shakespeare’s theatrical career. This laid a symbolic foundation for a future festival in this very city, dedicated to the author who changed English drama forever.

What is the Liverpool Shakespeare Festival?

The Liverpool Shakespeare Festival is an open-air theatrical event solely dedicated to the works of William Shakespeare. The festival first took place in 2007 and quickly gained cultural significance for the city, becoming a unique stage for contemporary interpretations of classical drama. It was initiated by the Lodestar Theatre Company, and its main venue has been the ruins of St. Luke’s Church, famously known as the “Bombed-Out Church.” This particular location creates an atmosphere difficult to replicate in a conventional theatre.

The festival’s format is a blend of classic performances and more experimental productions, sometimes featuring unexpected interpretations of the original text. The organisers strive for openness, so the action often spills beyond the traditional stage: streets, courtyards, even parks can become a setting. Sometimes, the audience even has the opportunity to participate in the performance.

The festival has another distinctive feature – it’s local in spirit but open to visiting troupes. Productions are prepared by both local companies and invited directors and actors from other cities. This ensures a constant exchange of ideas and styles. Some projects arise in collaboration with drama schools or community initiatives, providing young actors and amateurs with space for creativity too.

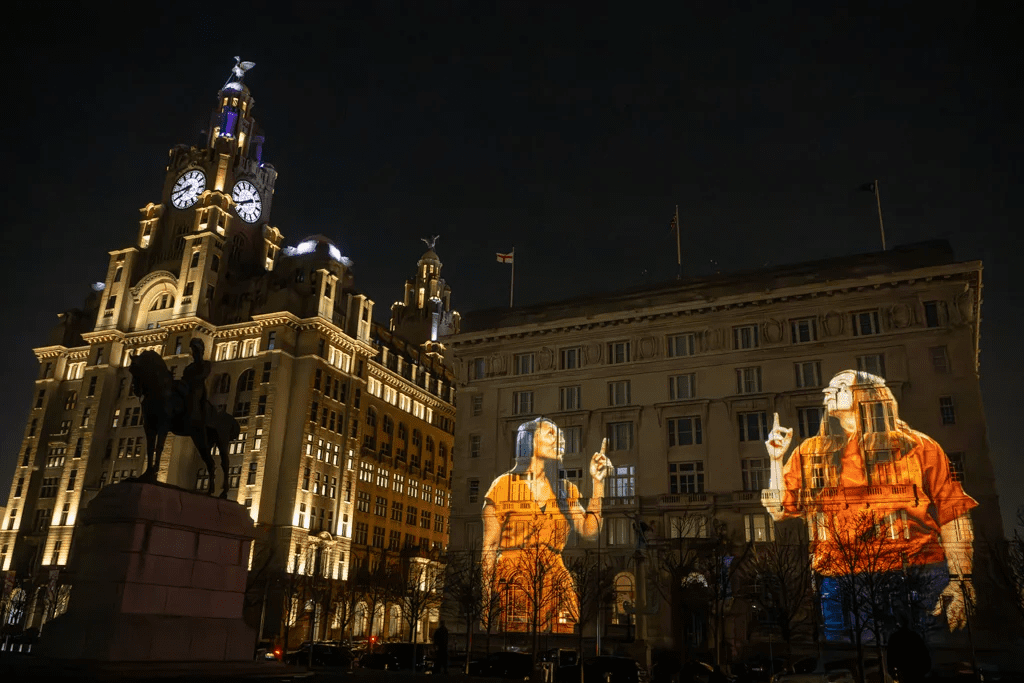

In Liverpool, Shakespeare isn’t placed on a pedestal – he’s simply released among the people. Here, he doesn’t hide behind the curtains of classical theatres but appears right in the middle of the city: in courtyards, by ruins, among passers-by. Furthermore, it’s not about recreating dusty antiquity – the important thing is to make the play speak directly to those who are here and now. And that’s precisely why this is a case where classic texts come alive in the hearts and minds of the audience.

From the History of the Liverpool Shakespeare Festival

Among the most interesting festival productions worth mentioning is “Macbeth” in 2007, where the shadows of the church ruins and St. James’s Cemetery created natural backdrops for the bloody drama. And in 2008, attendees were treated to “A Midsummer Night’s Dream”, utilising lanterns, live music, and interactive elements – the audience was even involved. Such decisions gave the classic text new colours.

In 2008, the festival became part of a larger celebration: Liverpool was then the European Capital of Culture. In addition to the “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” production with lanterns, live music, and actor improvisation among the audience, the city hosted a performance from Shakespeare’s Globe – “The Winter’s Tale”. That year, the festival expanded beyond the stage: open-air screenings were organised, local artists were involved, and an element of street celebration was added.

In 2009, they decided to play on contrast: staging “Hamlet” in the grand St. George’s Hall, and concurrently “Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead” at the Novas cultural centre. Both productions were performed by the same troupe, giving audiences the chance to see familiar actors in completely different roles. The festival received a prestigious local theatre award and established itself as an independent artistic event.

In 2010, the festival took a break due to funding issues. But the very next year, it returned with a bang: “Romeo and Juliet” once again came alive in St. George’s Hall, while amateur performances with local residents were held in parallel. One of the projects was an experimental production of “Richard III,” involving a hundred people – actors, students, and citizens.

Subsequently, the format expanded: the festival began to include masterclasses, readings, stage experiments, theatrical walks, and performances in unexpected locations. Crucially, both professional actors and those just discovering theatre worked side-by-side.

During this period, Liverpool was undergoing a kind of cultural revitalisation. While previously it was associated primarily with music, now theatre, and Shakespearean performances in particular, began to occupy a prominent place in the city’s life. The year as Capital of Culture provided a significant impetus, and the festival seized this opportunity.

From its very inception, the festival developed its unique language: it changed the very atmosphere of perception. Staging the classics wasn’t simple, but ultimately, new life was breathed into them, and they were integrated into Liverpool’s vibrant atmosphere.

How Liverpool Fostered Shakespeare’s Career

William Shakespeare’s name is usually linked with London, but his path to the big theatre stage might have been different without the support of a family… from Liverpool. This refers to the influential aristocrat Ferdinando Stanley, known as Lord Strange, heir to the Earls of Derby – precisely those who resided near Liverpool, in estates at Knowsley and Lathom.

Even at a young age, Ferdinando became a patron of a theatrical troupe that later became known as “Lord Strange’s Men.” This group toured throughout England, and in the late 1580s, began performing in London, at the first proper theatre on the South Bank of the Thames – The Rose. It was then, as historians surmise, that Shakespeare himself joined them – first as an actor, and then as a playwright.

Despite his short tenure, Ferdinando left a significant mark. His troupe not only paved the way for Shakespeare but also initiated a tradition of northern patronage in theatrical arts. Even after Stanley’s death, some actors transferred to the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, where Shakespeare was already playing a vital role.

Today, this connection to Liverpool inspires modern festivals, reminding us: art is never created in a vacuum. Even geniuses need those who believe in them from the start.

The Modern Festival and Shakespeare’s Historical Footprint in Merseyside

In 2016, Merseyside became one of the centres for commemorating the 400th anniversary of William Shakespeare’s death. Numerous theatrical productions took place in the region, including open-air performances by the Hillbark Players in Wirral, shows at the Everyman and Playhouse, and special children’s programmes like Bardolph’s Box. Furthermore, FACT cinema screened recordings of classic Shakespearean plays from London theatres, while festivals and projects like WoWFest broadened the audience, combining traditions with contemporary art forms.

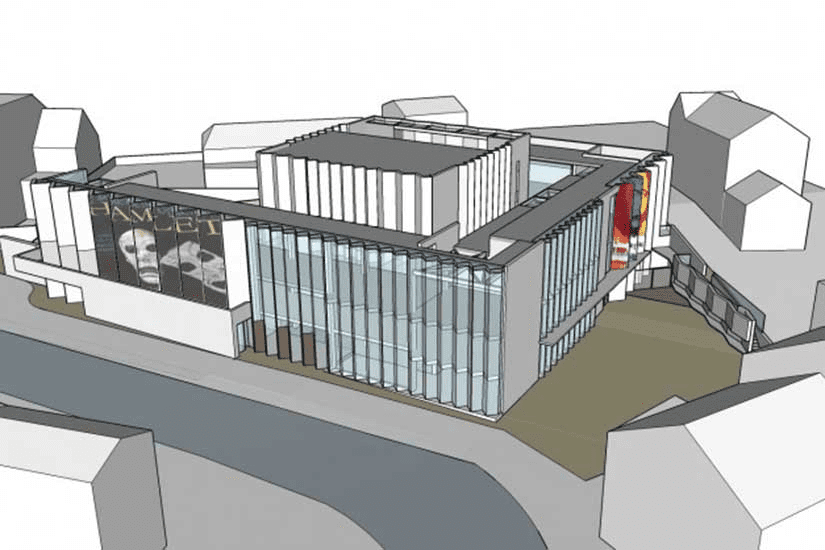

Merseyside has a deep historical connection with Shakespeare, who, according to some theories, spent time at Knowsley Hall, seeking refuge from the plague in London. In Prescot, in the 1590s, there was the only purpose-built Elizabethan-era theatre outside London, where productions were likely staged under the playwright’s own direction. Today, the Shakespeare North Trust plans to reconstruct this theatre based on 1629 drawings, creating a unique centre for learning and performances. Thus, history and modernity are closely intertwined, enriching the region’s cultural life.